There have been many breakthroughs made off the blood and sweat of Epidemiologists. They have been at the forefront of eradicating polio, smallpox, reducing deaths from cholera and even detecting thalidomide as a teratogen. But if you’re going to talk about the history of epidemiology, you have to start with John Snow.

John Snow was one of the first Epidemiologists, and he showed that cholera was water-borne, and debunked the (then-popular) Miasma theory. This Friday, organizations around the world will be marking his 200th birthday. I’ve listed a few events I’m aware of, but if your organization is hosting an event, comment with a link and I’ll add it below. Bonus points for those livestreaming or recording their events!

- The legacy of John Snow: Epidemiology yesterday, today & tomorrow, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

- The University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

- York University, Toronto, Canada

But lets talk about John Snow.

John Snow, The Father of Modern Epidemiology | Picture Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

John Snow was a British physician, born on the 15th of March, 1813. Born in one of the poorest regions of York in the United Kingdom. John Snow apprenticed as a surgeon, before becoming a physician in 1850 and moving to London.

Now, before we get into the Broad Street Pump story, we have to consider the context of the time. Pre-1900′s, the predominant theory behind disease transmission was the “Miasma theory.” In short, this theory suggested that diseases were spread through “bad air.” (Wikipedia link). It was an elegant, but incorrect theory that suggested that particles from decomposed matter would become part of the air, and this “bad air” spread disease. This was before they discovered that cholera was spread through Vibrio cholerae in water, thus debunking the Miasma theory (although it remains as a spell in Final Fantasy).

The Bacterium Vibrio cholerae | Picture courtesy the Dartmouth Electron Microscope Facility

Back to our hero. As the summer of 1854 wound down, a major cholera outbreak struck Soho, a neighbourhood in London, England. From August 31st to September 3rd, 127 people died of Cholera. Within a week, 500 people had died and around one in seven people who developed cholera eventually died from it. This all occurred within 250 yards of the Cambridge Street and Broad Street intersection.

John Snow came in and started his investigation.

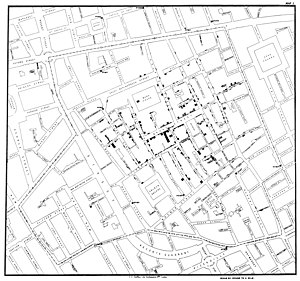

He examined the neighbourhood, and talked to everyone he could. He was looking for an underlying theme that linked these people together. He suspected some contamination of the water, but couldn’t find any organic matter in it, which you would expect under the Miasma theory. However, the more he looked, the more it seemed like the pump was responsible. Almost all the cases of cholera occurred close to the Broad Street Pump. There were only 10 cases that were closer to another pump. Of these, 5 preferred the water from the Broad Street Pump (and got their water from the Broad Street Pump) and 3 were children who went to school near the Broad Street Pump. The last two were unrelated, and likely just background levels of cholera in the population. This was pretty convincing, but Snow mapped it out to make sure that he was on the right track. You might recognize the map – it’s what we use for our blog banner here on Public Health Perspectives.

The map of all Cholera cases recorded by John Snow. Click to go to an interactive Google Map of the outbreak. | Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Snow provided more evidence for his theory that the pump was responsible for the cholera outbreak. For example, there was a brewery on Poland Street where 535 people worked, that had a pump on the premises. However, while cholera raged outside, only 5 of these people developed it. He explained this by pointing out that those who worked at the brewery were allowed to drink some of the malt liquor they made – and the foreman suspected that they didn’t drink any water at all. And even if they did, they used the pump on site.

The evidence Snow presented in favour of his findings were too compelling for the local council to ignore, and while there was resistance to this finding, Snow had said enough for the local council to remove the pump handle, halting the spread of the disease. But, as Snow later pointed out, he couldn’t be sure that this stopped the disease, and the incidence of the disease might have been declining. But the end result was the same – cholera cases went down.

That is not to say that everyone believed him. The council may have taken the pump down, but it wasn’t until 1885, when Robert Koch identified V. cholerae as the bacillus causing the disease that he had proof of his theory. He was right, but wasn’t around to see this discovery himself.

John Snow died on the 16th of June 1858, at the age of 45. His legacy still lives on, over a 150 years later. Epidemiology-related conferences still feature the Broad Street Pump in their logos and designs (http://www.epicongress2011.org/, http://csebottawa.ca/), and his story is one of the first budding epidemiologists hear. He has also been immortalized by the John Snow Pub at the corner of Broadwick and Lexington Streets in London, England (Google Maps link). Membership in the John Snow Society (http://www.johnsnowsociety.org/) requires you to visit the Pub – another reason to add that to your British vacation plans!

The John Snow Pub in London, England

While our techniques have advanced considerably since then, the basic principles established by Snow still exist in current Epidemiologic thinking. While some may argue that there were other pioneers of Epidemiology, including John Gaunt, Hippocrates and others, John Snow, if not the first Epidemiologist, is definitely one of the fathers of the field.

Note: A version of this post appeared originally on my blog at MrEpidemiology.com.